|

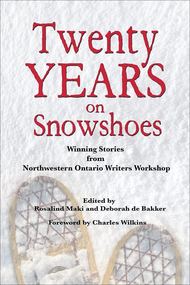

by Alex Kosoris I think I’m pretty safe in suggesting that writers want to improve their writing. That’s probably the biggest reason why I joined NOWW and started attending writing workshops, although that’s only a small part of training yourself to write better pieces. Practicing writing is the number one thing you can do, but it can be argued that reading is almost as important. If you read a lot, the act of reading as a casual observer will do wonders in and of itself, but I find value in taking things a step further. I try to delve deeper to find out why I feel this way as a reader, to hit on what the author did to lead me to a certain feeling or conclusion. If you make a point of at least trying this in your reading, you start to notice common techniques emerging across vastly different work, and it becomes easier to understand what an author did to make you feel a certain way – or what went wrong when you started to dislike a piece. Authors can take advantage of focused reading to improve a specific part of their writing. This can involve reading from a specific topic to ensure you aren’t writing over your head, or a specific genre in order to both understand what works within that style of writing and to ensure you don’t retread ground already familiar to fans of the genre. When submitting work to literary magazines and writing contests, it’s helpful to read previous winning entries to get an understanding of the makings of successful writing in order to direct the shape and feel of your writing for submission. NOWW has collected some of the winners from the annual writing contest in Twenty Years on Snowshoes, making it much easier for us to compare and contrast techniques. I find it hard to imagine a compelling story without a clean, strong plot. In rare cases, a talented writer can keep you on the edge of your seat with a story in which not much happens. But also consider how the story gets propped up or dragged down in the way the author handles characterization, pacing, and description. The contest format imposes constraints on the freedom an author has to tell a story, mainly through the word limit. My favourite stories in Twenty Years on Snowshoes come from authors who understand this, consciously or not, and either embrace it or push these boundaries successfully. Shorter stories necessitate a limit to the number of characters you have time to fully flesh out; if you include too many characters, it can hurt their personalities or their perceived realism, and, consequently, the story as a whole. The other main constraint that presents itself is in the complexity of plot. An author trying to do too much with a story with so little space puts the plot, the pacing, and the readers’ emotional response in peril. A sizeable number of the winning entries in fiction included in Twenty Years on Snowshoes share in the way vastly different stories are presented; for example: a story told through a naïve (often a child) narrator or protagonist with diverse themes, such as mourning, addictions, divorce, and closet lesbianism. Why does this technique work so well? I think that, by framing the story in this way, the author can influence the pacing by presenting bits of information through the point of view of someone who doesn’t understand the significance of what they see or experience. This allows the reader to slowly piece things together, injecting mystery and suspense into the narrative. It feels like a narrator is honestly telling us what little she learns or understands, rather than an author creating false suspense by refusing to reveal details. The big divergence amongst stories that employ this technique comes in the way the author treats this naive individual. My favourites in the collection go beyond the narrator as a casual observer, having them change as a result of the plot that they at least partially begin to understand by the end. In most stories using this style, the tragedy and drama happen almost out of frame, due to this lack of understanding from the key characters. By clearly influencing and changing them as we progress, this adds another tragic element up close: a loss of innocence. Of course, this isn’t to suggest what I’ve outlined here will be the only things you’ll discover when analyzing these contest winners, but, rather, that by asking yourself what makes the stories work for you will help shape and improve your own writing. Twenty Years on Snowshoes is available at all NOWW events and at Chapters. You can also call 345-0353 to get a copy. The cost is $20.  Alex was born and raised in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Between 2006 and 2010, he lived in residence in Toronto, Ontario while attending the Faculty of Pharmacy at the University of Toronto . In that period he discovered his love of writing, spending much of his free time writing short stories. Alexander expanded one of these stories into his first novel, Lucifer, Alexander posts reviews on the books he reads on kosoris.com, and regularly contributes to the Thunder Bay arts and culture magazine, The Walleye.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed