|

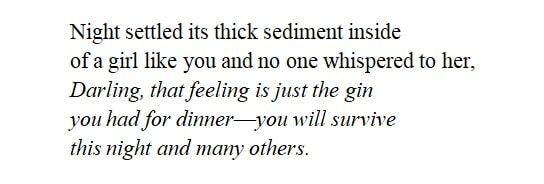

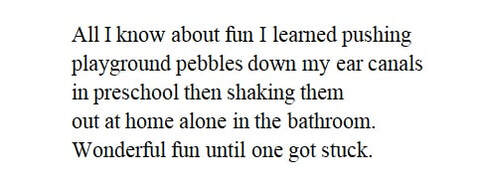

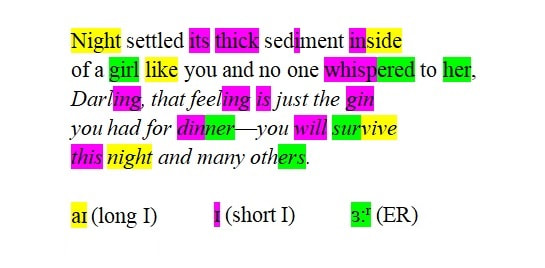

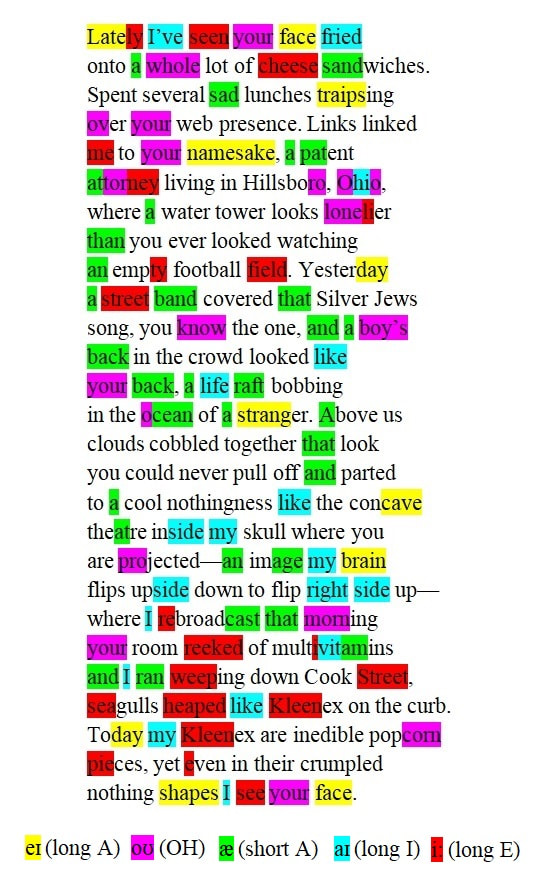

by Alexander Kosoris  I quite enjoy poetry, but it took a heck of a lot of reading to begin to get a sense of the styles I prefer within the form. And there’s something elusive about poetry. Even after years of active reading, I feel that I’m barely able to scratch the surface of understanding why certain passages speak to me. I believe that this is part of the explanation as to why the form can seem a bit daunting or even inaccessible. But every so often something comes along that allows a glimpse into the underlying techniques that make poems sing. In my recent poetry binge, Kayla Czaga’s Dunk Tankclearly showed me how sound repetition can be used to influence rhythm, pacing, and flow. And this specific aspect greatly interests me because it allows for subtle direction and structure that can be felt without jumping out at you, like more overt techniques employed to similar ends, such as tight rhyming or alliteration. I’ll illustrate what I mean and how this can be used with a handful of passages. In order to maintain specificity in the discussion, I’ll be using International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbols to describe various sounds, but I’ll give examples where possible for the sake of clarity. I want to start off with a passage that stood out to me on my first read-through. From the poem “Girl Like”:  Try reading it in your head and again aloud. Listen to the ebb and flow of the passage. Now look at it once more, with three common sounds highlighted: In this verse, aɪ and ɜ:rform a structural backbone, while ɪ is one of the driving sounds of the overall passage. The ɜ:rsound, specifically, punctuates the passage, while the overlap of sounds creates a blending effect that smoothes the flow. This technique can also be used to dictate pacing. For instance, refer to a passage from “Fun and Games”:  Note how the alliteration that moves between the first and second lines pulls your attention. But compare the final line. When I first read this, I found that I lingered there; the poem slows. Note how often the ʌ sound (UH, as in fun) occurs. This sudden build-up of one sound effectively slows the pacing, drawing attention to the concept presented, all without breaking flow overtly as when alliteration is used this way. I want to end with an entire poem with multiple repeating sounds highlighted, “Sleeping is the Only Love”: The eɪ sound never greatly builds up at any point in the poem, but it occasionally recurs, acting as a soft, cohesive point throughout, while the repetition of the sound in the first and final lines effectively underlines the common idea. The remaining four sounds are ever-present, heavily overlapping, but each increases in frequency at different times, each being the main driver of a subtle rhythm when this occurs. These, of course, aren’t the only recurring sounds within this poem. I invite you to consider the effect the frequently repeated ɪ sound creates with regard to the rhythm and pacing, or to look into consonant use throughout. (What does the strong use of the harsher S sounds at the start evoke compared with an increase in rolling Ls shortly thereafter?) The next time a poem stands out to you for reasons that aren’t readily apparent, try to look for repeated sounds and their relation to one another. And consider these sounds when writing your own poetry; you may end up with something musical. Alexander Kosoris is a book reviewer who regularly contributes to The Walleye, Thunder Bay’s arts and culture magazine.

“Girl Like,” “Fun and Games,” and “Sleeping is the Only Love” are taken from Dunk Tank, copyright © 2019 by Kayla Czaga. Reproduced with permission from House of Anansi Press, Toronto. www.houseofanansi.com.

0 Comments

The Challenge of Reaching out to Young Minds |

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed