How long have you been a member of NOWW? About three years. I was on the NOWW board for one year. What do you normally write? Young Adult – magical realism. Do you have a favourite book or favourite author? Don’t really have one – so many to choose from depending on my mood. Like everything from Ayn Rand to Calvin and Hobbes. Tell us a bit about yourself and how you found your way to writing: I started writing much in the same way I do anything in life – dive in and learn as you go! I threw myself into writing a YA magical realism trilogy having no experience in writing at all. Sure, I dabbled in writing here and there: Christmas letters, the odd children’s story for my kids. But nothing serious until I heard a story from a young child soldier in Uganda and felt very compelled—almost obligated—to share his story with the world. From then on, it has been writing and editing and learning ever since. Tell us a bit about your writing and your writing style: My Stones Trilogy (two are available now) are Young Adult magical realism novels suitable for anyone 12 and up. Although they’re considered YA, I have a lot of adults reading them too, which is nice because it means my stories are reaching a wide audience. I do a great deal of research for my novels: I read whatever books I can find on the subject, make notes that I refer to time and time again, and I go to the places I’m writing about. You can’t write about a subject as intense as Joseph Kony, the Lord’s Resistance Army, and child soldiers and have not visited Uganda at least once. I travelled extensively throughout the northern region of Uganda, interviewed many former child soldiers, including one of Kony’s wives and one of his body guards, and listened and watched and recorded everything. It was difficult at times because the stories were horrific but I felt, and still feel, very drawn to sharing these stories simply because they need to be heard. Right now, I’m finishing up book #3 in the Stones Trilogy and have a couple plans for another novel. I just came back from Malawi where I did some research on the child labour situation there and hope to put out a YA novel that will bring this dark subject to light for a teen audience. I would also like to return to Uganda to interview a woman I met who has an incredible story to share about her nine years of captivity with Kony and the LRA. Too many people gain recognition in the news for things that really aren’t newsworthy or admirable. I like to share stories about people who deserve to be heard, because of their courage and their actions, not because of their status or cruelty or stupidity. There’s enough of that in the world. Who has inspired and impacted your writing? My inspiration comes from the people I meet. When they have a story that needs to be shared I am compelled to write it. I’m not really inspired by any author. I like simplicity in stories though. Never been much of a descriptive writer or a poet, although I do enjoy it in other authors. My tip for writing? It comes from advice I gained from the ladies at Laughing Fox Writers, a local writing group I belong to: read five good quality books in the genre in which you wish to write. Read them again and study them with pen in hand. Make note of how things are done such as dialogue, description, action scenes etc. Absorb it all and then write. You’ll see a big change, a sort of “maturing” in your style. And you’ll like it. Where can we learn more about you and your writing? You can check out my website at www.donnawhitebooks.com and visit me on Facebook: donnawhitebooks, and twitter: donnawhitewrite, and Instagram: donnawhitebooks. I post a blog, every two weeks or so, on my website about my travels and interviews. My books, Bullets, Blood and Stones: The Journey of a Child Soldier and Arrows, Bones and Stones: The Shadow of a Child Soldier are available on Amazon as a paperback and as an ebook. You can also get them at Chapters/Indigo and Coles across Canada. Here in Thunder Bay you can also get them at Gallery 33 and The Bookshelf, and of course any author signing events during the year. You can see where and when I’ll be signing by visiting my author page on Amazon. And to end things off, tell us something surprising about yourself! I do a pretty mean turn on the barrels and can do a fine zig-zag through the poles during the local horse show gymkhana. However, I’ve had to put that part of my life on hold for a bit since I became busy with writing and teaching. Right now, the closest I get to barrel racing is riding my little black Arabian mare who is more or less shaped like a barrel due to lack of exercise. Oh well. Maybe next year.

0 Comments

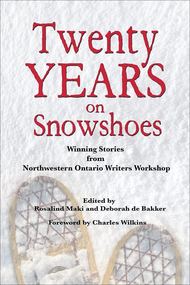

By Joan Baril We hung on every word. Joe spoke in parables, most taken from his own life. His tapestry of tales gave us information about writing memoir, along with a context to help remember it. He spoke about his time in the arctic, his early days at Lakehead University, his loves, his heartbreaks, all so personal and revealing that we, the listeners, just sat there, forgetting to take notes, our mouths hanging open. Soon we understood we were learning about memoir from Joe’s spoken memoirs. Joe related stories about his childhood in Westfort, his family, his early writing days, his column in the Toronto Star, his books, his first publisher. Joe told us about the career criminal, Ricky Atkinson, the leader of the Dirty Tricks Gang. Atkinson’s rough memoir became a book with Joe as co-author. Joe went round the circle asking the participants about their writing. Many were writers or poets or playwrights. Others planned to be. The woman who sat beside me was a painter with a good idea. She wanted to write the story of each painting. What a book that would make! Joe used these introductions to set up questions to answer later. Joe speaks slowly, softly, thoughtfully and also bluntly. The Westfort kid is still as tough as ever. When it was my turn, I said I wrote a few short memoir pieces, but to do so, I had to open a vein. He agreed. For him, it felt like slashing open an old sore on his arm, over and over. Joe rolled up his sleeve and pointed to the place where the ghost sore festered. Memoir is not for the faint of heart. I cannot retell his stories here. Too personal. They remain in that room. But I did make a few notes that I’ve tried to put in some kind of order. Of course, each participant in a workshop picks up what is personally relevant to them. I admit I spent a lot of my time jotting down side ideas that related to stuff I’m working on now. No doubt, others have a quite different set of notes from mine. Become an observer. Carry a notebook all the time. Go to places where people hang out and take notes. Go to the mall and watch. The patterns change over time. Annie Proulx hangs around her local bus station. You can too. There’s lots to see for a sharp observer. Hone your observation skills. Joe described spending an entire day on a Toronto street corner just observing. That day became a book, Rust is a Form of Fire. As a child, Joe was the watcher. Luckily for him, he came from a family of storytellers and became a storyteller himself. I believe he was a story collector from a young age. As a columnist, he talked to people to tease out their stories. He reads the obituaries, hunting for those true-life vignettes that stand out from the banal sweetness and obvious flim-flam of many death notices. (My note. In my opinion, the Winnipeg Free Press has the best obituaries.) Certain obituaries capture one’s imagination. You wonder what it felt like to be that person. Analyze why you’re attracted. What details move you? There is no such thing as writers’ block, says Joe. If you feel blocked go for a walk or go to the mall and observe deeply. Or write yourself a letter. Describe the problem. And most importantly, if you are blocked, you probably need more research. Writing. Keep the sentences short, one thought per sentence. Use clear, simple language. It must have cadence. Read it out loud. Read it out loud with a finger in your ear. (Why this works, I have no idea, but try it anyway.). You can teach yourself to recognize cadence just as you can teach yourself many elements of the craft. Read the King James’ Bible, a book swimming in cadence. Read or write poetry. Poets are a step ahead here because they are well acquainted with the beat and pulse of language. Start your piece with your best shot, the incident that you remember the strongest, the item that is the most memorable, that has the greatest punch. Joe says the New Yorker magazine taught him to give information clearly. He also likes cooking memoirs. A recipe is a model of concise and accurate writing. His goal is always accuracy and precision with laser-sharp details. Joe mentioned a technique called “squeeze and release.” You cannot keep the writing at a high pitch all the time. You must slow down, ease off, to give the reader a pause or a break. A reader can’t take too much power writing for long stretches. The question of dialogue came up. If you can remember it, use it. If it is in your notebook, all the better. If you can’t remember it, don’t make it up. It’ll sound phony. Never put modern phrases into the mouth of a historical character. Dialogue must be authentic to the times. Readers. What happens when we read? We follow the story by making pictures in our minds using out imagination. Therefore, as writers, we must aim to capture our reader’s imagination. Why do we read memoir specifically? Many reasons. Perhaps because we want a good story, or to learn something. Maybe to find out, “what it was like.” But readers can be our enemy. They get bored easily. They’re faithless. They sense when the writer is holding back, fudging the truth, skipping over information. The writer has to be fearless. The reader expects a point to the memoir. Otherwise they say to themselves, “Who cares?” There has to be a purpose that is clear and a resolution. Observation while reading. Everything you read, whether it be newspapers, advertising or books, is a teaching object. Be aware of how the piece affects you. Pause. Note your own reactions. Why did you get interested here, bored there? Mark the place where it happens. Analyze the section. Note the emotion or lack of emotion the writing evoked in you? Perhaps you sensed the author was faking it? If something works, try to figure out how it was done. If it doesn’t work, figure that out too and, as an exercise, rewrite it to make it better. Joe said he often rewrote the poems in the New Yorker to teach himself to be a poet. Detail, precise detail, is important but you can’t overload your work. There has to be space for the reader to imagine. By studying writing, you can become your own editor. It is hard to judge your own material but you can learn to do it. Do not surrender the task to anyone else. Do not give away your power. Getting to the Truth. You have to use journalistic methods. You must know that one person’s experience of the past may be different from your experience. Nevertheless, that does not invalidate your experience. You can use old photographs, diaries, cards such as condolence cards, and family letters. You can interview those who were present at the time. You can learn about the historical period. You can go back to the old house or visit the cemetery. Go to the sources. You are the Narrator. But who are you? You are the point of view in the story, the “I.” You are the focus. You have to be shameless, put yourself out there. The reader wants to connect with you. The reader will soon sense an inauthentic persona. You have to know yourself. Not always easy. You have to show your emotion. You cannot hide. When Joan Didion writes, she is the chief character in her book. Joe, as child and adult, is the main character in his award winning memoir, The Closer We are to Dying. He admits it was not an easy book to write. Joe’s Suggested Reading The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion. (in Brodie and Waverley libraries) Toast by Nigel Slater. Stet by Diana Athill. (in Waverley Library) The Way of a Boy: A Memoir of Java by Ernest Hillen. (in Brodie Library) Night of the Gun: a reporter investigates the darkest story of his life. (Brodie Library) The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White. (get the recent edition) The New Yorker magazine. (available at Chapters and in the libraries) Books by Joe Fiorito The Closer We Are to Dying (memoir) Rust is a Form of Fire The Song Beneath the Ice (fiction) Comfort Me with Apples: Considering the Pleasures of the Table. Union Station: Love, Madness, Sex and Survival on the Streets of the New Toronto The Life and Hard Times of Ricky Atkinson; Leader of the Dirty Tricks Gang by Ricky Atkinson and Joe Fiorito. First published in Joan Baril's blog : literarythunderbay.blogspot.ca  Joan M. Baril, is a short story writer who has had fifty-three fiction and nonfiction pieces published in literary magazines including Prairie Fire, Room, Northword, Anitgonish Review, Other Voices, CanadianWomen's Studies, Canadian Forum, Herizons, Ten Stories High, The New Orphic Review. She won several awards for her work including taking first place for short fiction in 2015 and 2016 in the North-western Ontario Writers annual contest. Her story, "The Yegg Boy' was nominated for the Journey Prize by the Antigonish Review. For several years, her columns on women's and immigrant issues appeared in the Thunder Bay Post and Northern Woman's Journal. In 1992 the Canadian government honoured her for her work with immigrants and for her column on immigrant issues. She has published articles in national magazines mainly Herizons and Canadian Forumn. by Alex Kosoris I think I’m pretty safe in suggesting that writers want to improve their writing. That’s probably the biggest reason why I joined NOWW and started attending writing workshops, although that’s only a small part of training yourself to write better pieces. Practicing writing is the number one thing you can do, but it can be argued that reading is almost as important. If you read a lot, the act of reading as a casual observer will do wonders in and of itself, but I find value in taking things a step further. I try to delve deeper to find out why I feel this way as a reader, to hit on what the author did to lead me to a certain feeling or conclusion. If you make a point of at least trying this in your reading, you start to notice common techniques emerging across vastly different work, and it becomes easier to understand what an author did to make you feel a certain way – or what went wrong when you started to dislike a piece. Authors can take advantage of focused reading to improve a specific part of their writing. This can involve reading from a specific topic to ensure you aren’t writing over your head, or a specific genre in order to both understand what works within that style of writing and to ensure you don’t retread ground already familiar to fans of the genre. When submitting work to literary magazines and writing contests, it’s helpful to read previous winning entries to get an understanding of the makings of successful writing in order to direct the shape and feel of your writing for submission. NOWW has collected some of the winners from the annual writing contest in Twenty Years on Snowshoes, making it much easier for us to compare and contrast techniques. I find it hard to imagine a compelling story without a clean, strong plot. In rare cases, a talented writer can keep you on the edge of your seat with a story in which not much happens. But also consider how the story gets propped up or dragged down in the way the author handles characterization, pacing, and description. The contest format imposes constraints on the freedom an author has to tell a story, mainly through the word limit. My favourite stories in Twenty Years on Snowshoes come from authors who understand this, consciously or not, and either embrace it or push these boundaries successfully. Shorter stories necessitate a limit to the number of characters you have time to fully flesh out; if you include too many characters, it can hurt their personalities or their perceived realism, and, consequently, the story as a whole. The other main constraint that presents itself is in the complexity of plot. An author trying to do too much with a story with so little space puts the plot, the pacing, and the readers’ emotional response in peril. A sizeable number of the winning entries in fiction included in Twenty Years on Snowshoes share in the way vastly different stories are presented; for example: a story told through a naïve (often a child) narrator or protagonist with diverse themes, such as mourning, addictions, divorce, and closet lesbianism. Why does this technique work so well? I think that, by framing the story in this way, the author can influence the pacing by presenting bits of information through the point of view of someone who doesn’t understand the significance of what they see or experience. This allows the reader to slowly piece things together, injecting mystery and suspense into the narrative. It feels like a narrator is honestly telling us what little she learns or understands, rather than an author creating false suspense by refusing to reveal details. The big divergence amongst stories that employ this technique comes in the way the author treats this naive individual. My favourites in the collection go beyond the narrator as a casual observer, having them change as a result of the plot that they at least partially begin to understand by the end. In most stories using this style, the tragedy and drama happen almost out of frame, due to this lack of understanding from the key characters. By clearly influencing and changing them as we progress, this adds another tragic element up close: a loss of innocence. Of course, this isn’t to suggest what I’ve outlined here will be the only things you’ll discover when analyzing these contest winners, but, rather, that by asking yourself what makes the stories work for you will help shape and improve your own writing. Twenty Years on Snowshoes is available at all NOWW events and at Chapters. You can also call 345-0353 to get a copy. The cost is $20.  Alex was born and raised in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Between 2006 and 2010, he lived in residence in Toronto, Ontario while attending the Faculty of Pharmacy at the University of Toronto . In that period he discovered his love of writing, spending much of his free time writing short stories. Alexander expanded one of these stories into his first novel, Lucifer, Alexander posts reviews on the books he reads on kosoris.com, and regularly contributes to the Thunder Bay arts and culture magazine, The Walleye. |

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed