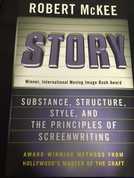

How long have you been a member of NOWW? I've been a member of NOWW since its inception. What do you normally write? My preferred genre is the short story and I have written dozens of them. Do you have a favourite book or favourite author? If I have to pick only one, my favourite author is Cormac McCarthy. His border trilogy and the two novels following are masterpieces and I can think of no other writer that matches him in style and content. Let’s get to know you a bit better. Tell us a bit about yourself, your writing journey and authors you’re drawn to? I always wanted to write. Ever since I was a youngster listening to bed time stories I yearned to be able you make up engaging fictions. However, for the most part, literature on school curriculums bored me. Most 19th century novels I studied in high school were dull. Jane Austen and Charles Dickens did not impress. Dostoyevsky, Blake and Hemingway had more appeal. Aside from Dylan lyrics, it wasn’t until grade 13 and studying the Theatre of the Absurd that writing began to appeal to my personal thinking. I liked Beckett and Albee and Tennessee Williams. Once I got out of school Henry Miller blew my mind. He was all about personal liberation. The tone was confessional, honest, and it transcended morality. I liked that. Then I wanted to be a poet and a song writer and failed miserably. In my early thirties I spent a winter at a cabin, alone. Although I had little ability, I began to paint and then write. I sent a bundle of stories off to Grain Magazine and they accepted one. Charles Wilkins liked a story of mine and included it in The Wolf’s Eye. I joined the Thunder Bay Writers Guild and learned how to be more objective with my own writing as well as others. I’m still at it and if I don’t write every day, I certainly think about writing and the story I am working on. Share your best writing tips: Fiction works if it has energy and emotion. Learn how to rewrite. Can we see you at any upcoming NOWW events? I hope to be attending some NOWW events this winter. I hosted a book launch at the Waverley Library for my new collection of short stories, Spirals, Stories of Northwestern Ontario. I am also giving a Critique Workshop with other members of the Thunder Bay Writers Guild on March 14th at the Waverley Library. Where can we learn more about you and your writing? I suppose members can learn more about me by reading my stories, writing to me at [email protected] or engaging me in conversation. I do not have a website or any other Internet address. My only previously published collection, The Truth Ratio by Emmerson Street Press, 2013, is now out of print but there are copies at two Thunder Bay libraries and I hope to put the book up on the web sometime in 2017. Other than that my work may be found in back issues of NOWW magazine and in anthologies by the Thunder Bay Writers Guild and in anthologies published by The Canadian Authors Association, Ten Stories High. Two anthologies published by Thunder Books in the 1990s also feature my work. Those books are entitled The Wolf’s Eye and Flying Colours And to end things off, tell us something surprising about yourself! Facts that may surprise: I am a hunter, a fisherman, and a gardener and try to follow the paleo diet. Although many of my fictional characters consume alcohol and abuse drugs, I no longer do either. I wrote a book of non-fiction last winter about the ground-breaking psychological insight of Canadian philosopher Sydney Banks. That surprised me. I will probably never publish it out of fear readers might think I am a New Age flake. Here’s a surprise: I admire Jesus, Buddha, Henry Miller and Bob Dylan, not necessarily in that order.

0 Comments

Picture Books: A Critique Checklist By Bonnie Ferrante One of the most difficult challenges of writing is revision and editing. We tend not to see our own mistakes. As well, there is so much to look at that even an experienced writer can feel overwhelmed trying to remember all the important points to assess. I have found it very helpful to use a checklist. While most people have an assessment method for novels and short stories, methods for critiquing a picture book are not as plentiful. I devised a list using a combination of other lists, writing books, classes, and personal experience. This checklist can be useful for critiquing group when only a few are experienced with reading large numbers of picture books. In fact, whenever someone submits a picture book to my blog (https://bferrante.wordpress.com/) for a review or for a critique in progress, I first record my initial reactions and then I bring out my checklist. I'm sure there are some things I've missed, but if you evaluate all of these you will have an excellent understanding of the suitability of the material for publication as a picture book. 1. Does the book have an intriguing or inviting beginning? Does the author get immediately to the point of the story or does she/he waste time on background information? Does the first page set up the entire story? 2. Is the book easy to read aloud? Does the vocabulary make you stumble? Is the language flat? 3. Is there a main character children can connect with or find interesting? Is that character dynamic and active? Does this character show change or growth? 4. Is the story direct and focused? Can you summarize it in one or two sentences? (This is valuable for the author to see how others have interpreted his/her work.) 5. Does the vocabulary and sentence structure suit the situation, mood, and theme? Is it interesting? Is it enriching? 6. Does the vocabulary suit the age level? Some challenging vocabulary in books that are not “I Can Read” style is encouraged. (There are differing opinions about authors using made up words. Personally, I think it only confuses the issue when children are trying to learn to read. I suppose after 33 years of teaching, I see children's books as a teacher first, a reader second, and a writer third.) 7. Is the book well paced? Are there slow parts? Are there parts that jump and feel missed? 8. Does the author show and not tell? Is there too much explaining? 9. Is the book diverse? Could there be children from different races? Are girls featured as well as boys? Are there stereotypes? 10. Is every word crucial? Are the nouns and verbs strong? Has the author avoided explaining things that can be shown in the illustrations? 11. Does the author ignite the reader’s senses? 12. Does the passage of time suit the story? Is it conveyed clearly? 13. Is there a clear beginning, middle, and end? Is the ending satisfying and logical? Would it make a child say: “Read it again”? 14. Does the story activate your imagination or thoughts? Does it stimulate visualization? Do you find yourself predicting or thinking about the situation? Do you continue to think about the book after you are finished? 15. If this story is written in rhyme, is it necessary? Is the story better without rhyme? In order to maintain the rhyming, did the author write unnatural or awkward sentences? Is the beat maintained throughout? Does the rhyming structure change for no reason? Is the rhyming innovative or is it predictable? 16. If there is a moral, does the text sound preachy? Does the author allow the child to use insight to glean the message? Is the tone upbeat and hopeful? 17. Does the child gain something from reading this book? Emotionally? Intellectually? Socially? Does the book provide something new to the child? Information? Viewpoint? Interpretation? Awareness? 18. Is the book within the recommended word count for picture books? (0 to 800 is acceptable, 500 to 600 is recommended, 1000 is rare.) Nonfiction books, especially those with text boxes, may be longer. If illustrations are included, answer the following questions: 1. Does the illustrator vary the point of view? Do they choose a point of view suitable to the accompanying text? 2. Is there a unifying link in the pictures or do they seem disconnected? 3. Is the style of illustration consistent throughout? Does it suit the story line? 4. Does the choice of colours suit the story mood, action, character or setting? Do they enrich the story? 5. Is the page size suitable for the age group in the story and for the illustrations? 6. Do the text and illustrations flow together well? Does the type font suit the story? 7. Is the composition satisfying? Does the page show enough to the reader? Does the page appear cluttered and confusing? 8. Do the pictures add to the story or are they redundant? (Some pictures should echo what is in the text but some pictures should further the story.) 9. Are the characters illustrated in a way that reflects what is written in the text? (Watch out for the dreaded brown-eyed girl who is drawn with blue eyes, for example.) 10. If the book is set in a certain time period, country, or culture, have the illustrations captured that correctly? 11. Do you enjoy looking at the pictures? Do they draw your attention? Are they satisfying? 12. Are the illustrations diverse? Are there children from different races, cultures, and abilities? Are girls featured as capable as boys? Are there stereotypes? Bio Bonnie Ferrante is a hybrid writer (published traditionally and self-published). Her work has appeared in various children’s and adult magazines and anthologies. She was a grade school teacher for thirty-three years, ten as teacher-librarian. Her focus is on YA novels and children's picture books. She loves reading at regional libraries, clubs, and schools. 1. What drew you to start writing poetry? When I was six years old I found an old high school copy of Macbeth that mother hadn’t returned when she dropped out at age 16. We had so few books in the apartment that I was immediately struck by it. When I began to read it I had never experienced language being used in that way (iambic pentameter). Even though I did not understand many of the words I could follow the story (I was transfixed by the image of a king being stabbed with daggers, a mad Queen Macbeth sleepwalking through a Scottish Castle, the three Weird Sisters chanting out their witches’ brew) and the rhythm of the language became inscribed, entrained in me somehow. I found my thoughts assuming the rhythms I had read in Shakespeare and I began to write them down. I suppose a poetic practice evolved from there. 2. Who are your biggest influences? Margaret Christakos, Lisa Robertson, Erin Moure, Ken Babstock, Dionne Brand, Marie Annharte Baker, Karen Solie, Aisha Sasha John, Shannon Maguire, Mat Laporte, Ariana Reines, Ben Lerner, Eileen Myles, Alice Notley, Bernadette Mayer, Gloria Anzaldua, Kathy Acker, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Sylvia Plath, Gertrude Stein, Rilke others I am no doubt forgetting. 3. You have a distinctive voice and you pay particular attention to line length, even though length can change dramatically from one poem to the next. Did you consciously develop this style? What prompts your choice of line length in each poem? I like to experiment with line length during the editing process. It is often a cue for me when reading how fast to jump from line to line, whether there will be a breath in between or there will be a breathless cascade of utterance. Sometimes its tied to the content of some poems (my more narrative poems often have short lines to stagger the listener/reader in an attempt to subvert the automatic immersion into story without a more nuances appreciation of language/line compression, etc.). I will decide on line length after trying out differing lengths and then reading each aloud, sometimes recording myself and listening back to confirm which sounds/”works” the “best.” 4. Your poem “Thinktent” harkens to the poets of the Romantic period when Wordsworth, Keats, and others explored themes of science vs. nature. You seem to be of two minds as well, a scientific lab researcher in your “day job” and a poet informed by your Anishnaabe heritage. How do you personally reconcile science, with all its good and bad, versus Nature? Is the world too much with us? I suppose I would say that I do not believe in Nature, the so-called Natural which is apart from and supposedly diametrically opposed in its “goals” in comparison to humans. Humanity and her worlds and fundamentally enmeshed with all other constituent beings in the dynamic ecology which is this known universe. Science is a way of interpreting the world as are the Anishinaabe traditions of reading the land, learning respectfully from plants and animals, and imploring the other-than-human world for guidance. I believe there are many ways that each of us can make sense of our worlds. I trained in Western science and still have a great respect for it but I have also tried to incorporate Anishinaabe views into my thinking and life practice. This is the basis, I think, of my poetics. 5. You mention in an interview with the Globe and Mail that you never thought of becoming a poet per se, and that you literally had an editor call you up with a book offer – every writer’s fantasy. How did it feel then to win the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize? As if I were simultaneously being pulled up into stratosphere and down into the earth’s molten core.  LIZ HOWARD’s Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent won the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize, the first time the prize has been awarded to a debut collection. It was also a finalist for the 2015 Governor General’s Award for Poetry, was longlisted for the 2015 Type Book Award, and received an honourable mention for the Alanna Bondar Memorial Book Prize. Her chapbook Skullambient (Ferno House, 2011) was shortlisted for the bp Nichol Chapbook Award. Born and raised in northern Ontario, Howard received an Honours Bachelor of Science with High Distinction from the University of Toronto, and an MFA in Creative Writing through the University of Guelph. She now lives in Toronto where she works as a neurocognitive aging research assistant. By Brandon Walker At the end of October, 2016, I was in New York City learning the fundamentals of storytelling from Robert McKee, a legendary script doctor/guru. McKee offers a three-day workshop based on his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting that is definitely worth the time and money. He teaches the form, not formula, for writing a good story. You may have heard of McKee and not realized it. The film Adaptation (2002) starring Nicholas Cage had a character inspired by McKee (played by Brian Cox), and McKee helped fix the third act of that script (please excuse the language). In my opinion, one of the most important lessons in this workshop was how you use subtext in dialogue. At the end of the second day, McKee talked about exposition – the history of your characters’ lives, the setting, and other important details you want to convey to the audience. “Exposition should be invisible. Show, don’t tell,” McKee said. Too often dialogue is written “on the nose,” meaning it directly expresses the characters’ thoughts and feelings. “It’s bad writing. If you write what the scene is really about then you’re in deep doo-doo. That scene will die like a squashed dog in the road,” he said. On the nose writing to convey that two people have known each other for years might be something like this: “I’m so glad we’ve kept in touch all this time. Gosh, we’ve known each other since high school. What has it been? 20 years?” Instead of that or “table dusting” – a scene with two maids dusting while chatting to pass exposition to the audience – McKee said you should use that information as ammunition. One friend should say to the other: “You’re the same immature ass that you were in high school.” Now you know they have been friends for years, and this presents the necessary conflict to keep the audience’s attention and keep the story interesting. McKee recommends bringing in exposition only when necessary, when the audience needs to know, including with flashbacks. Don’t be in a hurry, he said. Keep the audience in the dark a bit. At the start of the third day, McKee spoke more specifically about subtext. He described text as the sensory surface of a work of art. In this case, it’s the words on the page – what you see, hear, what the characters do. On the other hand, subtext is the inner life, thoughts and feelings of characters that are unexpressed, and their subconscious thoughts, too. “It’s impossible for humans to say and do what they’re thinking and feeling. The only time subtext should go into text is when you’re with a therapist, and even then the therapist is taking down what you’re not saying. Only crazy people speak the subtext,” McKee said. “Subtext is the stuff of acting. On the nose writing leaves nothing for the actors to do. Remember, the scene is not about what it seems to be about. As the audience, you become a mind reader, an emotion reader. You see the characters’ deep thoughts and feelings,” he said. This applies to writing short stories, novels, plays, TV shows and films, although McKee said stories and novels can allow the reader to hear the characters’ thoughts directly. So, what should characters say if they can’t speak their thoughts? McKee said the key is determining what characters want in the scene. For many characters, it’s conscious – they can name what they want. For instance, James Bond wants to kill the villain. “Dialogue must be economical – the maximum amount of content in the fewest words possible, with no repetition of language,” McKee said. Think of dialogue in terms of different beats of action and reaction. Beats are the strategies used by the character to try getting what he/she wants, and beats are also how the other characters react. Every scene should be a battle between at least two characters. As McKee said, progress can’t be made in a story except through conflict. He suggested working from the inside out by creating what is called a treatment. For each scene, write out the text and subtext without the dialogue – including the character’s thoughts and what they talk about – but don’t put words in their mouths yet. “Every scene must be perfect before you begin converting from scene description into screenplay. Then when you write the dialogue the characters won’t sound the same . . . and the dialogue will come out easily,” McKee said.  I highly recommend McKee’s books Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, and Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for the Page, Stage, and Screen. If you ever have a chance to attend one of McKee’s workshops, definitely go. There’s a reason why John Cleese, Julia Roberts, Kirk Douglas , David Bowie, and many other famous actors and writers have attended his Story workshop – he knows what he’s talking about.  How long have you been a member of NOWW? Since May 7, 2016 What do you normally write? I have written one non-fiction book, an autobiographical memoir. I don’t know if I will write much more. I am finding myself thinking about possibilities in the areas of creative non-fiction, history, or even a little poetry. Do you have a favourite book or favourite author? I don’t have a favourite author/writer as I am interested in many genres. I don’t have a favourite book, though I keep handy the Stephen Mitchell translation of the Tao Te Ching Let’s get to know you a bit better. Tell us a bit about yourself! I was born in 1942, and after growing up in Port Arthur, I went away to university and the military. I then returned to a life in the new city of Thunder Bay. Much of this time has been spent working on sexual minority and HIV/AIDS issues. It has also been an ongoing spiritual journey. Integrating sexuality and spirituality has been a major theme with variations. Other themes have emerged as well and some have evolved over time. Family and community, the military, union work, theatre, and impermanence have all been part of this lifelong journey. What has your writing journey been like and what areas have you focused on? From 1966 to 1976 I kept a journal on a couple of occasions and did a lot of scribbled writing. After that, any writing I did was focused on work. After taking part in a Wise Elders Circle at Lakehead Unitarian Fellowship which included a focus on harvesting one’s life and leaving a legacy, I was inspired to share my life story. The development of gay and HIV/AIDS community work in Thunder Bay is part of a social history that needs to be remembered. Having been part of the process, it has been my wish that my autobiographical memoir can be a contribution to that history. At the very least, I hope it may interest a few people as a chronicle of a Thunder Bay life that has made some positive contribution to community. What inspires you? Bob Dylan’s work has been an inspiration for me, and I am happy to see the Nobel Prize recognition. Allen Ginsberg has been another inspiration, along with many other writers. Mystery writers such as Joseph Hansen, Peter Robinson, Louise Penny, and others give me pleasure. There are too many writers to name. Major sources of inspiration for me include nature, music, and art. Can we see you at any upcoming NOWW events? I hope to attend and perhaps even participate in upcoming NOWW events. Stay tuned to find out which. Where can we learn more about you and your writing? I have a website www.davidbelrose.ca and a Facebook page www.facebook.com/differentcall. I have self-published Answering a Different Call: My (Queer) Thunder Bay Life available from me or various locations in Thunder Bay (Chapters, Fireweed, LU Bookstore, Thunder Bay Museum, Baggage Building arts Centre, Gallery 33). And to end things off, tell us something surprising about yourself! It’s all in Answering A Different Call. To find out more about how you can be featured in our Member Profile series, click here or email [email protected] |

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed