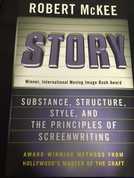

By Brandon Walker At the end of October, 2016, I was in New York City learning the fundamentals of storytelling from Robert McKee, a legendary script doctor/guru. McKee offers a three-day workshop based on his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting that is definitely worth the time and money. He teaches the form, not formula, for writing a good story. You may have heard of McKee and not realized it. The film Adaptation (2002) starring Nicholas Cage had a character inspired by McKee (played by Brian Cox), and McKee helped fix the third act of that script (please excuse the language). In my opinion, one of the most important lessons in this workshop was how you use subtext in dialogue. At the end of the second day, McKee talked about exposition – the history of your characters’ lives, the setting, and other important details you want to convey to the audience. “Exposition should be invisible. Show, don’t tell,” McKee said. Too often dialogue is written “on the nose,” meaning it directly expresses the characters’ thoughts and feelings. “It’s bad writing. If you write what the scene is really about then you’re in deep doo-doo. That scene will die like a squashed dog in the road,” he said. On the nose writing to convey that two people have known each other for years might be something like this: “I’m so glad we’ve kept in touch all this time. Gosh, we’ve known each other since high school. What has it been? 20 years?” Instead of that or “table dusting” – a scene with two maids dusting while chatting to pass exposition to the audience – McKee said you should use that information as ammunition. One friend should say to the other: “You’re the same immature ass that you were in high school.” Now you know they have been friends for years, and this presents the necessary conflict to keep the audience’s attention and keep the story interesting. McKee recommends bringing in exposition only when necessary, when the audience needs to know, including with flashbacks. Don’t be in a hurry, he said. Keep the audience in the dark a bit. At the start of the third day, McKee spoke more specifically about subtext. He described text as the sensory surface of a work of art. In this case, it’s the words on the page – what you see, hear, what the characters do. On the other hand, subtext is the inner life, thoughts and feelings of characters that are unexpressed, and their subconscious thoughts, too. “It’s impossible for humans to say and do what they’re thinking and feeling. The only time subtext should go into text is when you’re with a therapist, and even then the therapist is taking down what you’re not saying. Only crazy people speak the subtext,” McKee said. “Subtext is the stuff of acting. On the nose writing leaves nothing for the actors to do. Remember, the scene is not about what it seems to be about. As the audience, you become a mind reader, an emotion reader. You see the characters’ deep thoughts and feelings,” he said. This applies to writing short stories, novels, plays, TV shows and films, although McKee said stories and novels can allow the reader to hear the characters’ thoughts directly. So, what should characters say if they can’t speak their thoughts? McKee said the key is determining what characters want in the scene. For many characters, it’s conscious – they can name what they want. For instance, James Bond wants to kill the villain. “Dialogue must be economical – the maximum amount of content in the fewest words possible, with no repetition of language,” McKee said. Think of dialogue in terms of different beats of action and reaction. Beats are the strategies used by the character to try getting what he/she wants, and beats are also how the other characters react. Every scene should be a battle between at least two characters. As McKee said, progress can’t be made in a story except through conflict. He suggested working from the inside out by creating what is called a treatment. For each scene, write out the text and subtext without the dialogue – including the character’s thoughts and what they talk about – but don’t put words in their mouths yet. “Every scene must be perfect before you begin converting from scene description into screenplay. Then when you write the dialogue the characters won’t sound the same . . . and the dialogue will come out easily,” McKee said.  I highly recommend McKee’s books Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, and Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for the Page, Stage, and Screen. If you ever have a chance to attend one of McKee’s workshops, definitely go. There’s a reason why John Cleese, Julia Roberts, Kirk Douglas , David Bowie, and many other famous actors and writers have attended his Story workshop – he knows what he’s talking about.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed