|

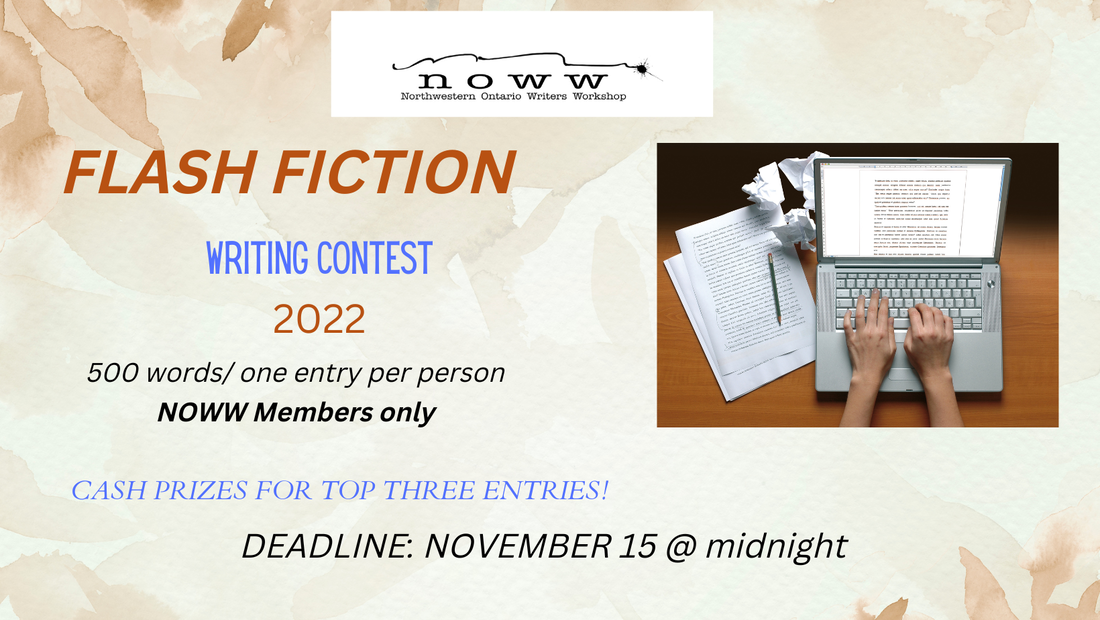

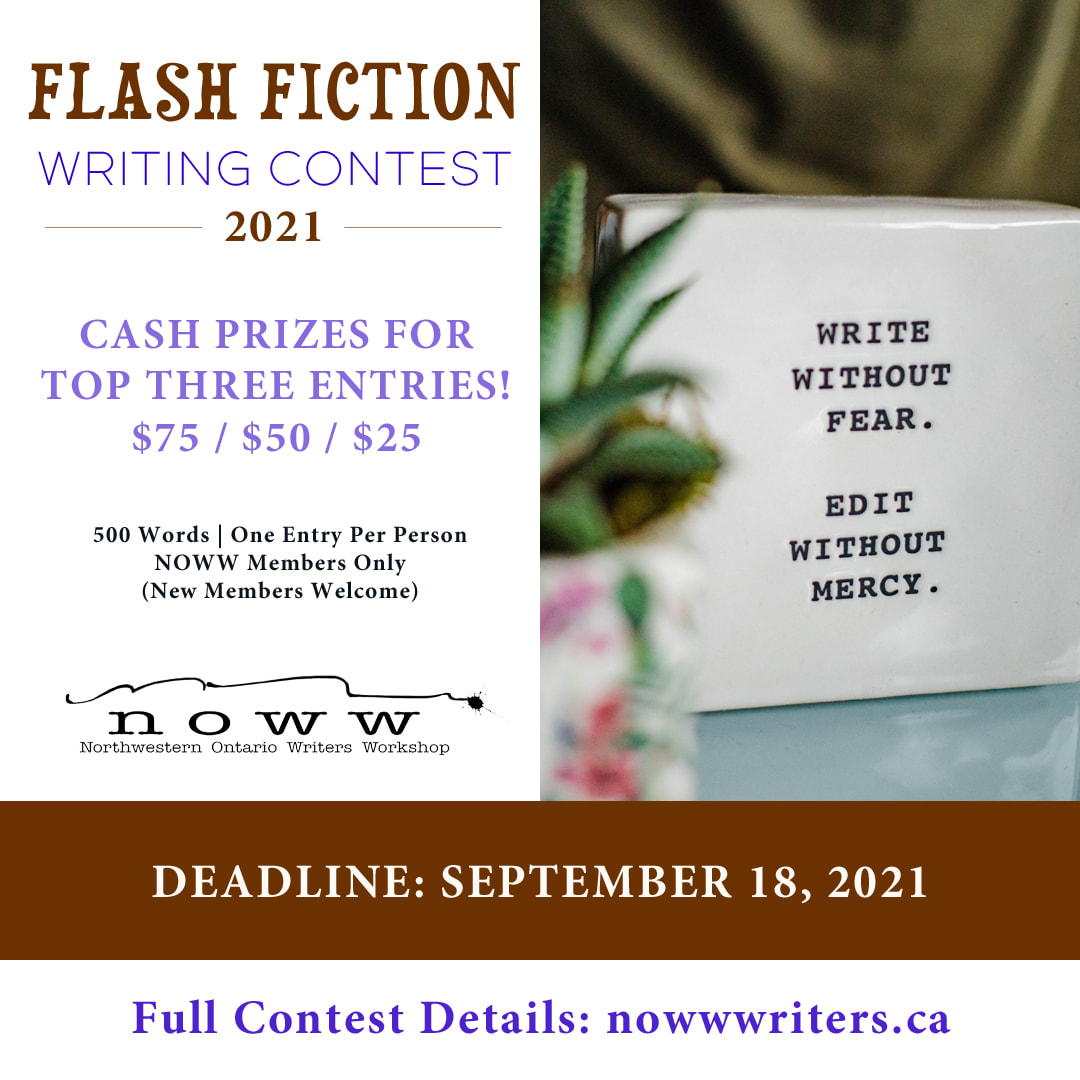

Challenge yourself with a little writing exercise, and you could win cash! The NOWW Flash Fiction Challenge is now accepting short short story entries of 500 words max. Quick and to the point! The top three stories will earn cash prizes and publication in our blog this fall.

Contest Rules

Two members of the NOWW board will judge the contest. What’s Flash Fiction? Flash fiction stories are, well, short. Sometimes called ‘micro-stories’, ‘postcard stories’ (if a postcard is part of the contest) or ‘short short stories’, flash fiction challenges the writer to fit a complete story into very few words. While there isn’t a paint-by-numbers formula for flash fiction, there is a certain art to it. It’s not about trying to squish a 3,000-word story into 500 words. Here are a few links to help you get a better idea of the craft—and to get the creative juices flowing: How To: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/may/14/how-to-write-flash-fiction(Another how-to written by David Gaffney) More Tips:https://www.hysteriauk.co.uk/2017/04/07/starting-flash-alex-reece-abbott/ (A UK contest with tips from the judges about how to write flash fiction) Some Examples:http://flashfictiononline.com/main/(Example pieces) NOWW’s Flash Fiction Challenge is a great way to challenge yourself and get the creative juices flowing. By the way, this blog post is 379 words, so you have a little more room than this to write your beginning, middle, and end. Think you can do it? Let’s find out! Start writing today!

0 Comments

The following excerpt is a sneak peek at the new novel by: Roy Blomstrom The Iterations of Caroline, out in February from Shuniah House Books. David (our narrator) and Caroline find themselves navigating Earth in different versions of the universe, pursued by Caroline’s ex-husband, who’s intent on killing them. In the episode below, David and Caroline are in different universes, and David has journeyed from Thunder Bay to the Pacific Coast of North America in the hope of finding Caroline again. The Iterations of Caroline Borderline/Brush Wolf The drive to Tulalip took less than fifteen minutes. In the casino, a set of totem poles stood in the center of the lobby. According to the explanations, at the top of the Story Pole, an eagle folded its wings around a creature with the head of a wolf and the body of a man. The creature symbolized all living things, human and wild, and the process of their transformation. It told the story of a time when humans and animals spoke the same language and shared the same culture. A memory hung just beyond my ability to call it forth. What the hell had drawn me to the casino? It had been a mistake to come. A conviction grew that something dangerous was going to happen. I was just about to leave when I remembered the dream—the jogger in Toronto at the beach, who’d said, “Look for the signs.” And the woman on the roof, who looked like Caroline, had said something about the brush wolf and the streetcar. Here I stood in a place I had no reason to be, looking at a pole topped with the animal of my fevered dream . “Drink?” I hadn’t seen the hostess approach. “Thanks, but no.” “Magnificent, isn’t it? I see it every day, and every day I find something different in it.” She stared up at it. “What do you see today?” “Today?” She thought for a moment. “Today my feet are hurting because of the heels they make me wear, and one of my kids has a fever and I’m worried about that, and all the lights and the sounds in the casino make this whole place seem unreal. I’m tired and I’ve got hours to go yet. Today, the totem is something solid, made of wood by someone who had something to say. It’s the most important thing in this whole place.” “Wasn’t there a sculptor who said he never made anything out of stone? He just chipped away to let what was inside it get out?” “Michelangelo. He’d have liked this. Let me know if you change your mind.” She left. I looked up at the totem again. Metaphor, Dr. Singh had said. Was the wolf turning into a man, or the man into a wolf? Would the transformation end up with a complete wolf and a complete man? Or was the transformation complete already, the creature in its final form, neither this nor that? In my dream, when I asked the woman on the roof where Caroline was, she’d said, “Damned if I know. I just walk them.” Them. # Maybe it was the wooden canoe outside the entrance of the casino. Maybe it was the sense that, at the ocean, change is the norm. Maybe simply because I’d never been to Ocean Shores. In any case, I wanted the water, the big expanse of the Pacific. I headed south, through Seattle and Tacoma, which hadn’t stitched themselves together in this world. Then on to Olympia, Aberdeen, and Hoquiam, each smaller than the place before. Ocean Shores—especially by the standards of this universe—was a surprisingly robust tourist community sitting on a long strip of sand. I expected something less commercial, more stripped down. I drove south along Point Brown Avenue past bars, antique shops, galleries, restaurants, hot dog stands and homes; then I angled onto Discovery Drive which, I discovered, became Marine View Drive and took me north before it meandered into Ocean Shores Boulevard. At last, I found a respectable-looking newer franchise motel. “Any rooms left?” I asked the clerk. He tapped a few keys on his computer and nodded without looking at me. “Ground floor or second?” “Do you have non-smoking?” “Yes.” “Non-smoking, please, on the second floor.” “Sorry, the only non-smoking room is on the ground floor. That okay?” He was forced to look up because I had decided to simply nod until he did. “That’s fine,” I said, to reward him. When he finished the paperwork, I asked, “How do I get to the beach from here?” “Go north, and when you get to West Chance a La Mer turn left. You can drive on the beach and park pretty much wherever you want. Continental breakfast,” he continued as if it somehow pertained to the beach, “is from six to nine in the Pirate’s Hall.” He pointed to a small open area behind me, its wall-mounted screen tuned to a golf channel. “You play golf?” “No, but a lot of our patrons do. Hope you enjoy your stay with us at Knightside.” I’d been dismissed. West Chance a La Mer was right where he’d said it would be. I drove onto the beach, where several hundred vehicles of all kinds sat in half a dozen crooked lines. It reminded me of pictures of Dominion Day celebrations in Port Arthur in the 1930s, when crowds of people who had no money to spend gathered at Boulevard Lake to meet friends and have picnics. North and south of where I’d left the asphalt for sand, the lines amalgamated, thinned, broke into sporadic clusters of cars and trucks, and then became widely spaced individual vehicles. I drove until I had a long stretch of beach to myself, then I got out. From my stash of camping equipment, I fetched a folding lawn chair and sat watching the waves break on the beach. In spite of my desire for the neverending vista of the Pacific Ocean, I’ve never been fully comfortable on an ocean beach. No matter how sunny and warm things are, no matter how far I can see, I always think about an approaching tsunami. When I drive toward a beach I note where the high ground is, in case I have to head for the hills. Most of the time I can control my fear, but when I find myself paying undue attention to the beach balls and surfboards, I know it’s time to leave. I don’t like being the kind of person who’d wrestle a beach ball away from some kid when a wave comes in and I need a life preserver. I kept my tsunami-watching paranoia more or less under control, and then the woman and her dog came by. I saw the dog first—I couldn’t help it. It had legs like a small pony and weighed at least a hundred and fifty pounds. Its steel-grey body was easily as tall as I was—then again, I was sitting in the lawn chair. Its massive chest and grizzled, rough-hewn head gave it an aura of power. It bounded along the water’s edge like a greyhound, then stopped suddenly where a wave retreated to sniff at something left behind, then doubled back to its owner, who jogged determinedly behind. Most dogs are single-minded when they find something to play with. Not this dog. When it saw me, it charged. “Clarence! Stop!” the woman yelled. The dog stopped and sat on its haunches a few feet away, looking down at me. I tried to look as unthreatening as possible. I couldn’t remember if that meant looking a homicidal dog in the eyes or playing corpse-in-a-chair. I chose to look at the owner as she approached. “Sorry about that. I hope Clarence didn’t frighten you.” She was trim and fit, younger than Caroline, one of those early-thirties women who make all their sentences end with a gravelly drop in tone. “No.” However, I noticed that my hands had gone, of their own accord, to guard the family jewels. As casually as I could, I moved my arms onto the armrests. “Okay.” She spoke to Clarence. The dog got off its haunches and padded slowly toward me, nose first. “Jesus, he’s big.” “Irish Wolfhound. Diana.” “You called him Clarence.” “He’s Clarence. I’m Diana.” “Yes, of course. Sorry. I’m—.” For a second I couldn’t remember if I was supposed to say Richard or David. “Richard Glendenning.” “Pleased to meet you, Richard. It’s okay to pat him. He doesn’t bite. He’s just a puppy and he likes to be petted.” If this dog wanted to be petted, I decided, I’d pet it. Clarence’s fur felt coarse. “Wolfhounds were used to hunt wolves, weren’t they?” That used up all the knowledge I had about wolfhounds. “In packs. His owner told me once that they were used in warfare, too, against the Romans or something. He isn’t mine, by the way—I’m walking him for a friend. Clarence thinks we’re hunting, though. It’s weird—like following a trail humans can’t see.” She laughed a little nervously, then asked the dog, “You’re hunting now, aren’t you?” He looked at her curiously, not quite sure what he was supposed to do. She turned back to me. “Wolfhounds were pretty well extinct by 1800 or so, but those left were bred with Great Danes, Mastiffs and Deerhounds, tailor-made to look like the original Wolfhounds but without the aggressiveness. Clarence here is really good with children. Aren’t you, Clarence?” The dog looked at her, glanced at the water, then returned to staring at her face. I said, “I think he wants to go back to hunting.” “Okay, Clarence.” The dog bounded off. “He loves running with other dogs when there are some around—plus pretending to be a brush wolf hunting ferocious shellfish.” I laughed. “Been nice talking to you. See you on the return trip.” She started off after the dog. For a while I watched her running along after Clarence. Then I closed my eyes for a moment. That was a mistake. I woke because the sun, which had been gently lowering itself into the blue-green water of the Pacific, had suddenly disappeared. Cold air, along with the crash of waves, shocked me awake. The sun hadn’t set, but it had gone behind low, dark clouds. The wind, stronger now, blew in gusts off the ocean. I shivered. It was time to go. I folded the lawn chair and put it in the trunk, then got in behind the wheel. As I reached for the armrest to pull the door closed, something hit the door with the force of a brawler’s kick and slammed it shut. I saw a snarling face at the window, paws scrabbling at the door. This wasn’t Clarence, a pretender to the title of Wolfhound. This dog was the real thing, the beast that made the Roman centurions flee. Its thick leather collar had inward-facing metal spikes. I looked beyond the teeth to see Diana, the dog-walker, running toward the car—carrying a leash made of chain. She clipped the leash to his collar and yanked him away. She mouthed “Sorry” as the dog snarled and barked. As I watched, she pushed down on his hindquarters to force him into a sitting position. After a second or two, she shouted “Home!” They headed along the beach, the dog trotting beside her obediently. I drove slowly across the beach to West Chance a La Mer and the Knightside Motel on Ocean Shores Boulevard. As I passed Diana and the dog she waved. I raised a hand in reply, a little too late for her to see it. My mind was on Bernie’s credit card. I hoped it still worked in this new world.  Roy Blomstrom was born in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), Ontario. He has published poetry, stories, and essays, and his ten-minute plays have been performed locally, in Finland, and at the Brighton Fringe Festival. He is grateful for support from the Ontario Arts Council for several works, including The Iterations of Caroline. He lives and writes in Shuniah, Ontario, where every day, he stares out at Lake Superior and wonders about the universe. by Marion Agnew What can I give you that will be of use in your next life, the one you will live without me? “At your age I wore a darkness,” Maggie Smith The ladder, its unvarnished wood cracked and splitting, rests on two walls in the corner of our bedroom. Its rails extend six feet toward the ceiling, connected by four rungs about twenty inches apart. I can wrap my thumb and middle finger around the rails at the top, but at the bottom, the rails are larger than my grip. A ladder repurposed as décor isn’t our usual style. You’d be more likely to see ladders in decorated-from-Pinterest homes, serving as bookshelves or towel racks. Our ladder isn’t furniture, though. It leans in the corner not only for what it holds, but also for what it is. # In a few years before and after 1970, when I was in elementary school, my mother scheduled her university teaching, research, and meetings so she could spend some afternoons with me at home. My siblings were mostly grown and gone by then. And while Mom trusted me to be a responsible “latchkey kid” most days, she didn’t feel right about leaving me alone at home after school every day. Oklahoma’s afternoon light crept through the patio’s sliding glass doors to illuminate the family room. The wood-paneled walls embraced chairs of dark wood, upholstered in the then-popular avocado-and-orange earth tones. I’d sit sideways in the harvest-gold recliner, twisting my too-straight, too-fine, so-long-it’s-tangled hair as I read. On the adjacent sofa, my mother spread the contents of her crocheting bag—skeins and balls of yarn plus her work-in-progress. She’d learned various needle arts as a girl in the 1920s and 30s, sewing clothes for her dolls. As a young woman, she knit sweaters for her older brother and needlepointed floral-and-navy-blue chair covers. Crocheting and knitting had experienced a grand resurgence in the late 1960s, and Mom embraced it. At 4 PM, I’d put down my book. In the hour before I had to leave for swim practice, Mom and I watched Perry Mason reruns on TV. Mom enjoyed mysteries and had read many of Erle Stanley Gardner’s books. She approved of Raymond Burr as Perry and Barbara Hale as Della Street. However, she often said that William Hopper was too good-looking to be Paul Drake, their private investigator. Still, she thrilled, as I did, when Paul showed up in the last moments of the trial. He’d exchange a significant look with Della and whisper something to Perry that changed the direction of the case, letting Perry tie up loose ends and restore justice in the world of TV reruns. # My grandfather, Mom’s father, made the ladder that stands in the corner—perhaps ninety years ago, perhaps only seventy—from trees he’d cut down to clear space for the camp. He stripped the bark and sanded the rails so they’d feel good under his hands. For the rungs, Grandpa chose thick, sturdy lengths and large nails to minimize the chances the rungs would split while bearing his weight. For decades, the ladder stood or lay outdoors, its feet or rails in snow, damp leaves, mud, moist earth. Lichen and mold grew on the rails. It’s difficult to tell what kind of wood it’s made of—it’s weathered grey now, and the rails don’t hold obvious traces of branch patterns—but spruce, balsam fir, and even cedar are possibilities. Some paint residue, shades of Atomic Tangerine and Plum, cling to its surfaces, where I cleaned brushes while repainting the camp. # Mom’s fingers knew how to crochet, even while she watched TV. She made granny squares—a pattern starting with a small square of double-crochet stitches around a circular eye. The design grows as you add concentric, square-shaped “rounds.” The finished squares, usually four or five rows, are sewn together into a larger fabric to cover pillows or serve as blankets. Now cliché and used as TV-show shorthand to signify working-class families, granny squares can also be very attractive. Some people choose colours carefully, to complement a specific palette. Mom’s squares, though made carefully and well, were a hodge-podge of colours, like a wildflower meadow in bloom. Through a year or two of Perry Mason reruns, she made dozens of squares of different colour combinations, unified by a final row of black. Eventually, she sewed them into a blanket as a gift for my sister, who lived on campus. # I don’t know why I imagined Grandpa’s old ladder as décor. We favour sentiment and comfort over a more intentional aesthetic, but I’m as susceptible as anyone to Pinterest, I suppose. Besides, I wanted to incorporate an object from Grandpa’s era into our home. But as my birthdays have accumulated, I’ve become increasingly aware of how quickly time passes. Improvements to the camp that my husband and I made “recently” are showing their age after fifteen years. Exterior and interior paint and roof patching would all be welcome. The floor under the piano needs to be shored up again. In the face of such impermanence, I needed to choose my treasure quickly. A significant advantage of the ladder as an heirloom was its portability. I couldn’t remove the peeled-spruce posts holding up the inside roof, the wall paneling from a grain car, or the wavy-glassed windows. Through the years, the ladder had already made the transition from tool to artifact. Long ago, Mom had bought safer aluminum ladders to use. I found it hard to watch the wooden ladder rotting, returning to the dirt the trees had originally grown in. So I rescued it—to use it again, but differently. I carried the ladder from the camp to our house, where I left it on the porch “for a little while” that became a full year, while I pondered what to do with it. In the summer of 2020, I reconnoitered. About a foot of the bottom of each rail, plus the bottom rung, were rotten beyond reclaiming, so I took the chainsaw to them. Sandpaper got rid of rough spots and lichen, and it otherwise cleaned up well. According to Mom, Grandpa never imagined that our property, ten acres and two camps, would still be in the family after all these years. I’m not sure Mom was right about that. After all, Grandpa gave her the smaller camp after she’d gone away to graduate school, before she married. Was it a tether to ensure she’d return, at least occasionally? She did, of course, and our place sustained her through the decades when she could spend only a few weeks here each summer. But Mom did have a point. Grandpa barely met me—he died when I was an infant—so he couldn’t predict that I’d torque my life’s path and come here to live. He could never have known how this place would continue to challenge and reward me. What’s harder to accept: Mom never knew, either. # A mathematician, Mom prized order and symmetry, and she was a born problem-solver. During Perry Mason’s commercial breaks, we puzzled over motive, means, and opportunity. Who could be lying? Whose alibi was suspect? What would Perry’s court strategy be? We talked about her crocheting, too—did she have enough yarn of this colour for this square’s fourth row or only the second? Did olive green or teal look better with this dark scarlet? Would this butterscotch complement the row of cream or make it look jaundiced? Our time with Perry Mason came to an end as I grew up. But Mom still enjoyed crocheting. Eventually, she started a blanket for me—hexagons this time. We both enjoyed the silliness of the phrase “granny square hexagons.” Though I am a writer, not a mathematician, I too solve problems. I puzzle over memories. I know some facts about her gift to me. Hexagons, the choice of bees for their honeycombs, make for sturdy yet lightweight structures. My blanket, ninety-eight hexagons in total and edged with four black, lacier rows, has also endured. Over the years, it’s become pilled and worn, and some of the colours have faded unevenly, but it’s otherwise intact. Though facts remain, many of my specific memories are lost in the past. No matter how intently I look, I can’t see Mom’s darning needle, threaded with black yarn, flashing in and out as she sewed the completed “hexagonal squares” tight. I can’t remember when she gave me the finished blanket. I was probably in high school, when I never made my bed. I do remember the blanket from other eras. In the years after my first marriage, I draped it over the back of the one chair (also harvest gold) in my bare-bones apartment while I read assignments for graduate school. I wrapped myself in it on winter evenings while crying over my stupid decisions, over my brave ones. My mother’s fingers, nimble before her knuckles grew arthritic, wound and caught and do-si-doed yarn into knots in orderly rows. Then the finished blanket disappeared into the larger fabric of my life. It became part of the background, largely taken for granted. As was she, until her memory began to unravel permanently. She switched from crocheting to knitting, and I was grateful that knitting sometimes eased her fretfulness and anxiety. She continued to knit increasingly uneven squares until late in her disease. At a day program she attended to give my caregiver father some respite, she brought needles and yarn and taught several of the workers there to knit. # Traditionally, ladders symbolize the connection between Heaven and Earth, the divine and the mundane. In the Abrahamic religious traditions, Jacob dreamed of a ladder, with angels ascending and descending, and received a prophecy of a promised land. “Jacob’s Ladder” is the title of a song—several songs, actually, some by rock bands as well as the moving spiritual sung by enslaved African and Black peoples in North America. Novels and movies, trails and landmarks and sections of highway, a specific type of pocketknife and a mathematical surface all bear the name. It’s a pattern for a quilt square and a cascading ribbon-and-wood-block toy. Jacob’s Ladder is also a figure in the Cat’s Cradle, an ancient game found in many cultures that involves a length of string tied in a circle. Working with a partner, you take turns looping the string around your fingers to form different images. The eighty-plus Perry Mason murder mysteries depend on a ladder—“The Murderer’s Ladder,” a plotting tool Erle Stanley Gardner developed. It considers the killer’s very human motivations and temptations; how those feelings might engender a plan; and then, given the opportunity, how they could lead someone to take the next step, and the next. A ladder’s construction echoes its purpose. Its two rails are linked by rungs, and a ladder links space on the ground to space above or below, or, when it’s laid between structures, connects this space to that one. The very structure of our DNA, the spiral staircase of the double helix, is a type of ladder. # For many years of winters in this house, Mom’s blanket lay on the end of the guest room bed, waiting to welcome me on nights made restless by hormones or snoring. Summers, I’d fold it and set it on the closet shelf to wait for the first snow, when I’d bring it out to air before draping it on the bed. As summer became autumn in 2020, an unsettling season in a tumultuous year, I brought Mom’s blanket down from the guest room shelf. Again, I unfolded it and smiled at its colours—the flame-orange and pewter-green of lichens; its hues of moss and bark, blueberries and snowflakes, granite and quartz and basalt. In our own bedroom, I re-folded the blanket and hung it over a rung of the ladder, its wood silvered like the winter sky and summer twilight. As sunlight wanes and waxes with the seasons, I press my palm to the ladder’s rails. With a finger, I trace the outline of a colourful hexagon. I find comfort and continuity, even in this time of great uncertainty. It’s what he made. It’s what she made. These are the things they gave me, that are of use in this life, the one I live without them.  Marion Agnew’s personal essays are collected in Reverberations: A Daughter’s Meditations on Alzheimer’s, published by Winnipeg’s Signature Editions in 2019. It was shortlisted for the Louise di Kiriline Lawrence award for nonfiction. Her writing has received support from the Ontario Arts Council and been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and a National Magazine Award. She lives in Shuniah, mere yards from Lake Superior, and is unduly proud of her prowess with loppers and chainsaw. Are you ready to transform your writing practice and make space for writing in your life forever? Sign up for my FREE live masterclass to slide one step closer to bringing the joy and excitement back to your writing life. We have your back! Saturday, October 30th, 2021, 11am PST WHAT YOU WILL LEARN FROM THIS MASTERCLASS:

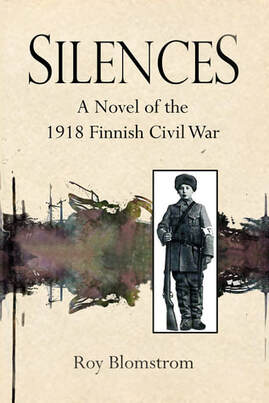

Learn from award winning author, writing coach, and literary agent  Chelene Knight Chelene Knight is the author of the award-winning memoir, Dear Current Occupant. Her novel, Junie is forthcoming Fall 2022. Chelene is currently writing a book on Black self-love and joy commissioned by HarperCollins Canada. Register at: www.breathingspacecreative.com/mindset-reset Reverberations: A Daughter’s Meditations on Alzheimer’s By Marion Agnew Signature Editions (Oct 1, 2019) ISBN: 9781773240589 (softcover) ISBN: 9781773240602 (Kindle ebook)  My mother recently passed away after a battle with Parkinson’s-related dementia, so I wasn’t sure what effect Marion Agnew’s book, Reverberations A Daughter’s Meditations on Alzheimer’s, would have on me. As I read, it soon becomes clear that the author had a difficult relationship with her mother, Jeanne LeCaine Agnew. Why wouldn’t she? The woman was an Ivy League mathematician, a neutron transport equations researcher during WWII, a university professor, and a demanding mother of five known by friends as “the meanest mom ever.” It’s also apparent, however, that when her mother began to slip away due to the ravages of a terrible, insidious disease, Agnew longed for much more. And as she shares her story of love and loss, I begin to recall the changes in my own incredibly strong mother. The diseases aren’t the same, but the longing for more time and the sadness experienced from helplessly watching the slow erasure of abilities and personality are. I’m also drawn in by what Agnew chooses to share with us. Her meditations, often unflattering, are so very human and underline something she states in the mathematical language preferred by her mother: “Let d be the distance between us.” Reverberations is a mémoire—a collection of essays that reflects the writer’s own experiences and memories. It covers various chapters of her life but always seems to come back to times she spent on the western shores of Lake Superior. As she recalls the summer weeks she stayed at the family’s Northwestern Ontario cottages each year, Agnew ponders how her life and relationships change within the framework of her mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s. There’s much sadness here, yet we also see humour (the many conflicting ways to make perfect devilled eggs), the defining and deepening of the author’s love for her parents, the realization of her dream to live full-time on the big lake, the kindling of an autumn romance, and the arrival of a certain understanding … “Summer or winter or somewhere in between, when I’m outdoors I can hear sounds of our human life as if they’re present. Voices of the lake, and rowboats. Letters rustling, beach rocks plunking, music, leaking roofs. The voices of people, children and adults, related to me and not, who mow and rake and prune and dig and cut, who nail and paint and scrape, who sweep and bake and roast and polish the stove, who connect water lines and empty the outhouse pails, who row and paddle and pole and swim and splash. Who dream, and plan, and pay. And love. Perhaps somewhere, somewhen, my mother walks the beach and picks up a bit of granite or jasper, an agate, a piece of pink driftglass. Perhaps she thinks of me. We, and our echoes and reverberations, for better and worse, are part of the undersong.” Marion Agnew has given us an honest and touching look at the human condition, and I recommend taking the time to read it. Marion Agnew’s essays and short fiction have appeared in numerous magazines and literary journals, including The Malahat Review, The New Quarterly, Atticus Review, The Walleye, The Grief Diaries, Full Grown People, and the anthologies Best Canadian Essays 2012 and 2014. She has been shortlisted for the Prairie Fire contest as well as a Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Originally from Oklahoma, she realized her dream of becoming a Canadian citizen and moving to her family’s summer property in the Canadian Shield, where she had spent the most magical summers of her childhood. Clayton Bye NOWW President  Silences by Roy Blomstrom Publisher: Shuniah House Books (Nov. 23, 2017) Language: English Paperback: 269 pages ISBN-10: 1775052621, ISBN-13: 978-1775052623 A Reflection

Silences begins with the discovery of a man’s body dangling from a hanging tree on the outskirts of Port Arthur in 1955. One shoe on. One off. The story shifts back to northwest Finland in the early 1900s. We meet two rural families, one Finnish speaking and the other Swedish speaking Finns. Things get complicated when a small shop owner is killed in what at first glance seems like a senseless attack. One marauder loses a boot in the process. The violence turns out to be a precursor to a civil war between the reds and whites, imported in part from Russia. War envelopes both families in conflict, leaving some dead and others damaged irreparably by what they’ve lived through. It’s particularly cruel to a 15-year-old boy who volunteers for the white army as a cook. His older brother is killed in a brutal battle for Tampere. When his body is found, he’s missing one boot. The trauma follows the survivors across the sea when they migrate to Canada. During the hot summer of ’55, two mismatched boots appear in the window of a local shoe repair shop. Appears the killer is in Port Arthur. The hanging is the culmination of the journey for one combatant. Silences uncovers a devastating period in Finnish history. The magnitude of the tragedy is staggering. People who had lived in peace for years suddenly commit terrible atrocities in the name of ideology. The impact of external powers like Russia and Germany shows how smaller nations can be treated as pawns in greater geopolitical conflicts to terrible effect. The story also gives a clear depiction of posttraumatic stress disorder. Long before such a diagnosis existed, the characters have to learn not to judge others or their behaviour. It’s a lesson that’s as true now as in 1955. Silences kept me intrigued. I love a good mystery. It also appealed to my historical curiosity. But more so, it made me think of the human condition, the terrible consequences of war, and the incredible ability of people to cope with the unimaginable. The story made me think and feel. What more can you ask of a novel? Patrick Peotto Can you pack a whole story into just a few paragraphs? Of course you can! The NOWW Flash Fiction Contest is now accepting short-short story entries of 500 words max. Quick and to the point. The top three stories will earn cash prizes ($75/$50/$25) and publication in our blog this fall. Contest Rules

Two members of the NOWW board will judge the contest. WHAT IS FLASH FICTION? Flash fiction stories are, well, short. Sometimes called “micro-stories”, “postcard stories” (if a postcard is part of the contest) or “short-short stories”, flash fiction challenges the writer to fit a complete story into very few words. While there isn’t a paint-by-numbers formula for flash fiction, there is a certain art to it. It’s not about trying to squeeze a 3,000-word story into 500 words.

Here are a few links to help you get a better idea of the craft—and to get the creative juices flowing: How To: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/may/14/how-to-write-flash-fiction (Another how-to written by David Gaffney) More Tips: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/writing-101-what-is-flash-fiction-learn-how-to-write-flash-fiction-in-7-steps (This article actually lists only six steps – perhaps to prove the point?) Some Examples: http://flashfictiononline.com/main/ (Example pieces) Still I Rise: Book Review by Sue Blott Can a whole book consist of one forty-three line poem and still be strong and bold enough to hold one’s interest? If the poet is Maya Angelou, undoubtedly. Can the art of one man successfully echo the sentiments of this strong poet? If the artist is Diego Rivera, certainly. Even the cover stirs the soul. Diego’s painting is of a seated woman, hands fisted on her crossed knees, her gaze unflinching and upward, flanked by two workers, also gazing upward. Diego chose to draw the woman and the two people from a low angle, looking up at them looking up. Then the book’s title, Still I Rise, sits below the painting in yellow contrasted on a green background. Holding the book, I feel a holy Hell! Yes! Immediately I know the book will pull no punches but that it will ultimately uplift the soul. This small solid square book is all about rising up. Most pages consist of a segment of the poem on one side of the page and a vertical or horizontal painting on the opposite page. Earthy colours such as brick red, clayish yellow and sap green plus a clear deep blue highlight each two page spread. So it comes down to the selection of the painting versus the words. How in sync is the selection? And how can such strength be equally portrayed as a marriage instead of as two powerful pieces of work each vying for attention or overshadowing each other? The poem’s segment length varies so the poem is anything but static. Sometimes a whole stanza is illustrated ie Out of the huts of history’s shame/ I rise/ Up from a past that’s rooted in pain/ I rise/ I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,/ Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.Other times, a mere two lines: Did you want to see me broken?/ Bowed head and lowered eyes? So does the selected painting accurately reflect the chosen words? The temptation is to find a coupling that is weak or a little off. A crack in the marriage. But it’s impossible. A couple spring to mind, but mine them deeper, both the words and the painting, and their juxtaposition beautifully compliments each other. Take the lines: You may kill me with your hatefulness,/ But still, like air, I’ll rise. Appropriately written on a sky-blue page with a full-page sized portrait on the opposite page of Portrait of Dolores Olmeda, 1955, at first the portrait seems distanced from the words, especially the images of hate and death. But the woman looks fresh and hopeful. Clad in a bright flowered dress with a headband of flowers and ribbons woven in her hair, she carries a cloth-bottomed basket filled with mangoes. Her gaze is unyielding, forward-facing, steady and confident. She holds the abundant future, ie the ripe fruit, in one arm and lifts the flounce of her dress with her other hand. No restrictive clothing will hold her back. Her resolve seems strong and firm. No doubt that she’ll rise clear- eyed and firm of foot. Then there are the pairings that resonate so well they seem to vibrate off the page. For instance, You may shoot me with your words,/ You may cut me with your eyes,/ is paired with the picture Mural Study of Hands, Chapingo, 1927. The picture shows a close up of a woman’s left hand clasping just under the wrist of her right hand which in turn cradles her chin. Such a unique coil of connection. The woman’s shoulder-length curly black hair and her mouth and nose are evident but the painting ends, interestingly, below her eyes. Intriguing but, as such, it emphasises the critical world’s eyes, not the woman’s eyes. Likewise the portrait, Portrait of Ruth Rivera, 1949, which accompanies the lines: Does my sexiness upset you?/ Does it come as a surprise/ . Ruth Rivera is painted in a simple white dress that suggests her hips. She glances over her shoulder while holding a beautiful round mirror filled with golden light and her profile. She looks as though she was admiring herself when someone walked in the room but she shows no surprise, more a look of indignation of being dis- turbed. The mirror glows moon-like, subtly emphasis- ing the feminine and the mysteries of femininity. To reach the height needed, the mirror’s long handle is taped to another stick, a surprising attention to detail when noticed in the gorgeous murkiness of the lower background. Ruth’s sandaled foot peeks from under her dress as though she were postulating to no-one but herself, admiring her own beauty and strength. The following page quivers with vitality. Complimenting the couplet That I dance like I’ve got diamonds/ At the meeting of my thighs?/, it is the only painting that features men. Dance in Tehuantepec, 1935 shows a man and a woman dancing barefoot while seated women watch. The man, all in yellow with a black hat, kicks and leans back while the young woman with twirling blue ribbons in her hair, has both feet solidly on the ground, her white skirts lifted and swaying about her ankles. In the distance, a second couple echoes the main dancers’ postures. The paint- ing vibrates with a passion that totally matches such brazen words and uplifts the heart, the way a good dance and hypnotic music is apt to do. This little book shows no qualms at cutting be- tween stanzas to shift the kilter, to toss us off balance. Despite this, I think Maya Angelou would approve even though it may give a slightly different interpre- tation to her work. Interestingly, the poem doesn’t ap- pear intact, on one page in the book, forcing the reader to take it however it is presented, piece by piece, page by page, digesting every word. Rivera’s paintings are listed in the back of the book and cover a range of years from 1924 to 1955. Angelou’s poem appears to have first been published in 1978. This book was first published in 2001. The difference in times forms an inspiring arc, a multilayered umbrella of creativity. The back cover of the book has no words, only a repeated painting: Nude With Calla Lillies (Desnudo con alcatraces), 1944. A naked woman kneeling on a woven mat embraces a huge basket overflowing with white calla lilies. She could be embracing the book itself! Its softness provides a refreshing contrast to the gritty industry of the front cover painting suggesting that woman still rises, on her own terms, through her own strength. She embraces the lilies as hope and assurance that yes, she will rise, whatever it takes. What a joy for anyone to experience this little gem of a book. More especially, perhaps, what a joy for a creative. At least for this writer, the joy of cre- ating is in the process but also in the unknown, the release of a piece into the world at some point, some- how. One never knows when creating something how, when or even if it will breathe on its own, who it will journey to, who it will uplift, who will cling to it like a life raft in a dark stormy sea, what it could be paired with. Perhaps it could be argued that a female artist’s paintings, maybe even different artists, should have illustrated the poem. Yet, it’s hard to fault any of the pairings—this little book simply works as a support- ive marriage. In wondering how Maya Angelou and Diego Rivera would have viewed this book, I think they would have both approved, probably as true cre- ative souls, neither of them surprised by the delightful combination of support and strength from each other’s work. Perhaps, as it is meant to do, this small book would have uplifted their souls.  Sue Blott has been writing for as long as she can remember, in as many different genres as possible. She isdelighted to have won this prize for her review of a small book crammed with hope and power; a fitting anthem for these turbulent days.

|

NOWW Writers

Welcome to our NOWW Blog, made up of a collection of stories, reviews and articles written by our NOWW Members. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed